Nicholas Wade, former science reporter for the New York Times has written a book, A Troublesome Inheritance, in which he argues that large-scale societal differences (e.g., the existence of capitalist democracies in the West or of paternalistic, authoritarian political systems in Asia) may be attributable to small genetic differences that were fixed at a population level through the action of natural selection since the emergence of anatomically modern humans and their subsequent dispersal from Africa. The fixation of these gene variants happened because the continents of Europe, Asia, and Africa (homes of the major "racial" groups) differed in systematic ways. David Dobbs recently reviewed it in the Sunday Review of Books, which prompted a kind of amicus brief letter-to-the-editor from over 120 population geneticists, affirming that Wade's writing misrepresents the current science of genetics. A full list of the signatories of this letter can be found here. It is a veritable who's who of contemporary population genetics.

As you might imagine, A Troublesome Inheritance has been quite controversial. A great deal has already been written on this book, both in formal publications and in the science (and economics) blogging ecosystem. To name just a few, Greg Laden, my old homie and fellow TF for Irv DeVore's famous Harvard class, Science B-29, Human Behavioral Biology, wrote a brief review here for American Scientist. Columbia statistician and political scientist, Andrew Gelman, wrote a review for Slate.com. Notre Dame professor and frequent contributor of popular work on human evolution, Agustin Fuentes, wrote a critique for Huffington Post, while UNC-C anthropology professor Jonathan Marks wrote a critique for the American Anthropological Association blog, which also appears in HuffPo.

Honestly, I think that Wade's book is so scientifically weak and ideological (despite his protestations that science should be apolitical) that it is likely to have a very short half-life in contemporary discourse on human diversity and science more broadly. In fact, I have advocated to the editorial boards of professional societies to which I belong not to do anything special about this book since I'm confident it will be soon forgotten for its sheer scientific mediocrity. I find it interesting that the great majority of the people who like the book seem not to be scientists but comment on Wade's "bravery" for spurning "political correctness" and the like. There are substantial parallels here to public debate over climate change or vaccination: the professional conclusions of the scientists who actually work on the topic only matter when they correspond with the social, political, or economic interests of the parties engaging in the debate. What do geneticists know about genetics anyway? So, it is with some hesitancy that I write about it, but my colleagues' letter has reminded me of a larger beef I have with the contemporary state of human evolutionary studies. This beef boils down to the fact that most contemporary students of human evolutionary biology know next to nothing about genetics. I've actually encountered a number of leading figures in human behavioral biology who maintain an outright hostility toward genetics. This is a topic that my colleague Charles Roseman and I have grumbled about for a few years now. We keep threatening to do something about it, but haven't quite gotten around to it yet. Perhaps this is a humble start...

This state of affairs is extremely problematic since genetics is the material cause (in the Aristotelean sense) or one of the mechanistic causes (in the Tinbergian sense) of much of the diversity of life. If we are going to make a scientific claim that some observed trait is the result of natural selection, we should be able to have a sense for how such a trait could evolve in the first place. The standard excuse for ignoring genetics in the adaptive analysis of a trait of interest is what Alan Grafen termed the "phenotypic gambit." The basic idea behind the phenotypic gambit is that natural selection is strong enough to overcome whatever constraints may be acting on it. The phenotypic gambit is a powerful idea and it has yielded some productive work in behavioral ecology. I use it. However, a complete evolutionary explanation of a trait's existence needs to consider all levels of explanation. In modern terms, and as nicely outlined a letter by Randolph Nesse, we need to answer questions about mechanism, ontogeny, phylogeny, and function. Explanations relying on the phenotypic gambit only address the functional question (i.e., fitness, or what Tinbergen called the "survival value" of the trait).

I could go on about this for a long time, so I will limit myself to three points: (1) complex traits will generally not be created by a single gene, (2) heritability and the response to selection are regularly misunderstood and misapplied, (3) we need to think about the strength of selection and the constancy of selective regimes when making statements about the adaptive evolution of specific traits.

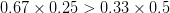

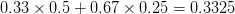

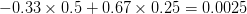

First, we need to get over the whole one-gene thing. Among other things, the types of adaptive arguments that are made particularly for recent human behavioral innovations are simply highly implausible for single genes. There are a variety of formulae for calculating the time to fixation of advantageous alleles that depend on the particulars of the system (e.g., details about dominance, initial frequency, mutation rate). Using the approximation that the number of generations that it takes for the fixation of a highly advantageous allele with selection coefficient  is simply twice the natural logarithm of

is simply twice the natural logarithm of  divided by

divided by  , we can calculate the expected time to fixation for an advantageous allele. With a (very) substantial average selection coefficient of

, we can calculate the expected time to fixation for an advantageous allele. With a (very) substantial average selection coefficient of  (think of lopping of 5% of the population each generation), the time to fixation of such a highly advantageous allele is about 120 generations generations. That's over 3,000 years for humans. This is interesting, of course, because it makes the type of recent evolution the John Hawks or Henry Harpending have discussed more than plausible. It makes it hard to imagine how the large changes in presumably complex behavioral complexes in historical time suggested by authors such as Wade or Gregory Clark, author of Farewell to Alms (which I actually find a fascinating book), pretty implausible.

(think of lopping of 5% of the population each generation), the time to fixation of such a highly advantageous allele is about 120 generations generations. That's over 3,000 years for humans. This is interesting, of course, because it makes the type of recent evolution the John Hawks or Henry Harpending have discussed more than plausible. It makes it hard to imagine how the large changes in presumably complex behavioral complexes in historical time suggested by authors such as Wade or Gregory Clark, author of Farewell to Alms (which I actually find a fascinating book), pretty implausible.

In addition to the population-genetic implausibility of single-locus evolutionary models, complex traits are polygenic, meaning that they are constructed from multiple genes, each of which typically has a small effect. Now, this doesn't even address the issue of epigenetics, where genotype-environment interactions profoundly shape gene expression and can produce fundamentally different phenotypes in the absence of significant genetic difference, but that's another post. In many ways, this is good news for people who study whole organisms in a naturalistic context (like human behavioral ecologists!) because it means that we can work with quantitatively-measured trait values and apply regression models to understanding their dynamics. In short, the math is easier though, admittedly, the statistics can be pretty tricky. Further good news: there are lots of people who would probably be happy to collaborate and there are plenty of training opportunities in quantitative genetics through short courses, etc.

The masterful review paper that Marc Feldman and Dick Lewontin wrote for Science in 1975 amid the controversy surrounding Arthur Jensen's work on the genetics of intelligence, and its implications for racial educational achievement differentials, still applies. Heritability is a systematically misunderstood concept and its misuse seems to surface in policy debates approximately every twenty years. Heritability, in the strict sense, is a ratio of the total phenotypic variance that is attributable to additive genetic variance (i.e., the variance contributed by the mean effect of different alleles). Because total variance of the phenotype is in the denominator of this ratio, heritability is very much a population-specific measure. If a population has low total phenotypic variance because of a uniformly positive environment, for instance, there is more potential for a greater fraction of the total variance to be due to additive genetic variance. Think, for example, about children's intelligence (as measured through psychometric tests) in a wealthy community with an excellent school district where most parents are college-educated and therefore have the motivation to guide their children to high scholastic achievement, the resources to supplement their children's school instruction (e.g., hiring tutors or sending kids to enrichment programs), and the study skills and knowledge base to help their children with homework, etc. I have used this example in prior post. Given the relative uniformity of the environment, more of the variation in test scores may be attributable to additive genetic contributions and heritability would be higher than it would be in a more heterogeneous population. This is a hypothetical example, but it illustrates the rather constrained meaning of heritability and the problems associated with its application to cross-population comparisons. It is also suggestive of the problem of effect sizes of different contributions to phenotypic variance. The potential for environmental variance to swamp real additive genetic variance is quite large. What's a better predictor of life expectancy: having a genetic predisposition to high longevity or living in a neighborhood with a high homicide rate or a endemic cholera in the drinking water supply?

Heritability essentially measures the potential response to selection, everything else being equal. The so-called Breeder's Equation (Lush 1937) states that the change in a single quantitative phenotype (e.g., height) from one generation to the next is equal to the product of heritability and the force of selection. If there is lots of additive variability in a trait but not much selective advantage to it, the change in the mean phenotype will be small. Similarly, even if selection is very strong, the phenotype will not change much if the amount of additive variance is low. A famous, but frequently misunderstood result, known as Fisher's Fundamental Theorem shows that the change in fitness is directly proportional to variance in fitness. This is really just a special case of the breeder's equation, as shown in great detail in Lynch and Walsh's textbook (and their online draft chapter 6) or in Steve Frank's terrific book, in which the trait we care about is fitness itself. An important implication of Fisher's theorem is that selection should deplete variance in fitness -- and this makes sense if we think of selection as truncating a distribution. A corollary of Fisher's theorem is that traits which are highly correlated with fitness should not have high heritability. Oops. Does this mean that intelligence, with its putatively very high heritabilities is not important for fitness?

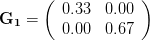

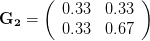

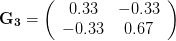

Everything in the last paragraph applies to the case where we are only considering a single trait. When we consider the joint response of two or more traits to selection, we must account for correlations between traits (technically, additive genetic covariances between the traits). Sometimes these covariances will be positive; sometimes they will be negative. When the additive genetic covariance between two traits is negative, it means that selection to increase the mean of one will reduce the mean of the other. In their fundamental (1983) paper, my Imperial College colleague Russ Lande and Steven Arnold generalized the breeder's equation to the multivariate case. The response to selection becomes a balancing act between the different force of selection, additive genetic variance, and additive genetic covariance for all the traits. Indeed, this is where constraints come from (or it's at least one place). Suppose there are two traits (1 and 2) that share a negative covariance. Further suppose that the force of selection is positive for both but is stronger on trait 1 than it is on trait 2. Depending on the amount of genetic variance present, this could mean that the mean of trait 2 will not change or even that the mean could decrease from one generation to the next.

The work of Lande and Arnold (and many others) has spawned a huge literature on evolvability (something that Charles has moved into and that we have some nascent collaborative work on in the area of human life-history evolution). This work is very important for understanding things like the evolution of human psychology. Consider the hypothesis, popular in evolutionary psychology, that the mind is divided into a large number of specific problem-solving "modules," each of which is the product of natural selection on the outcome of the problem-solving. How do you create so many of these "organs" in a relatively short time frame? Humans last shared a common ancestor with chimpanzees and bonobos around five million years ago and most likely human ancestors until about 1.8 million years ago seem awfully ape-like (and therefore probably not carrying around anything like the human mental toolkit in their heads). One of the key processes responsible for the creation of complex phenotypes is known as modularity (which is a bit confusing since this is also the term that evolutionary psychologists use for these mental organs!) and one of the fundamental mechanisms by which modularity is achieved is through the duplication of sets of genes responsible for existing structures. These duplicated "modules" are less constrained because of their redundancy and can evolve to form new structures. However, the fact that modules are duplicated means that they should experience substantial genetic correlation with their ancestral modules. This makes me skeptical that the diversity of hypothetical structures posited by the massive modularity hypothesis could be constructed by directional selection on each module. There is just bound to be too much correlation in the system to permit it to move in a fine-tuned way toward to phenotypic optimum for each module.

Trade-offs matter for the evolution of phenotypes. While I suspect that very few human evolutionary biologists would argue with that, I think that we generally fall short of considering the impact of trade-offs for adaptive optima. The multivariate breeders' equation of Lande and Arnold gives us an important (though incomplete) tool for looking at these trade-offs mechanistically. A few authors have done this. The example that comes immediately to mind is Virpi Luumaa and her research group, who have done some outstanding work on the quantitative genetics of human life histories using Finnish historical records.

My third, and last (for now), point addresses the constancy of selection. This is related to the concept of the Environment of Evolutionary Adaptedness (EEA), central to the reasoning of evolutionary psychology. A few years back, I wrote quite a longish piece on this topic and its attendant problems. Note that when we use population-genetic models like the one we discussed above for the expected time to fixation of an advantageous allele, the selection coefficient  is the average value of that coefficient over time. In reality, it will fluctuate, just as the demography of the population selection is working on will vary. Variation in vital rates can have huge impacts on demographic outcomes, as my Stanford colleague Shripad Tuljapurkar has spent a career showing. It can also have enormous effects on population-genetic outcomes, which shouldn't be too surprising since it's the population of individuals which is governed by the demography that is passing genetic material from on generation to the next!

is the average value of that coefficient over time. In reality, it will fluctuate, just as the demography of the population selection is working on will vary. Variation in vital rates can have huge impacts on demographic outcomes, as my Stanford colleague Shripad Tuljapurkar has spent a career showing. It can also have enormous effects on population-genetic outcomes, which shouldn't be too surprising since it's the population of individuals which is governed by the demography that is passing genetic material from on generation to the next!

When I read accounts of rapid selection that rely heavily on EEA-type environments or the type of generalizations found in the second half of Wade's book (e.g., Asians live in paternalistic, autocratic societies), my constant-environment alarm bells start to sound. I worry that we are essentializing societies. One of the all-time classic works of British Social Anthropology is Sir Edmund Leach's groundbreaking Political systems of Highland Burma. Leach found that the social systems of northern Burma were far more fluid than anthropologists of the time typically thought was the case. One of the key results is that there was a great deal of interchange between the two major social systems in northern Burma, the Kachin and and Shan. Interestingly, the Shan, who occupied lowland valleys, practiced wet-rice agriculture, and whose social systems were highly stratified were seen by western observers as being more "civilized" than the Kachin, who occupied the hills, practiced slash-and-burn agriculture, and had much more egalitarian social relations. Leach (1954: 264) writes, "within the general Kachin-Shan complex we have, I claim, a number of unstable sub-systems. Particular communities are capable of changing from one sub-system into another." Yale anthropologist/political scientist James Scott has extended Leach's analysis in his recent book, The Art of Not Being Governed, and suggested that the fluid mode of social organization, where people alternate between hierarchical agrarian states, and marginal tribes depending on political, historical, and ecological vicissitudes is, in fact, the norm for the societies of Southeast Asia.

The clear implication of this work for our present discussion is that a single lineage may find some of its members struggling for existence in hierarchical states where the type of docility that Wade suggests should be advantageous would be beneficial, while descendants just a generation or two distant might find themselves in egalitarian societies where physical dominance, initiative, and energy might be more likely to determine evolutionary success. I don't mean to imply that these generalizations regarding personality-type and evolutionary success are necessarily supported by evidence. The key here is that the social milieux of successive generations could be radically different if the models of Leach and Scott are right (and the evidence brought to bear by Scott is impressive and leads me to think that the models are right). At the very least, this will reduce the average selection differential on the putative genes for personality types that are adapted to particular socio-political environments. More likely, I suspect, it will establish quite different selective regimes -- say, for behavioral flexibility through strong genotype-environment interactions!

These are some of the big issues regarding genetics and the evolution of human behavior that have been bothering me recently. I'm not sure how we go about fixing this problem, but a great place to start is by fostering more collaborations between geneticists and behavioral biologists. Of course, this would be predicated on behavioral biologists' motivation to fully understand the origin and maintenance of phenotypes and I worry that the institutional incentives for this are not in place.