Following our recent Nature paper, there has been a flurry of press, some of which I reference in a previous post. There is a very nice article that gives the back-story of SIV research at Gombe at MinnPost.com. Put this together with Carl Zimmer's post and you get a good sense for how research unfolds in a situation like ours...

Category Archives: Infectious Disease

New Publication: Chimpanzee "AIDS"

A long-anticipated paper (by me anyway!) has finally been published in this week's issue of Nature. In this paper, we show that wild chimpanzees living in the Gombe National Park in western Tanzania on the shores of Lake Tanganyika appear to die from AIDS-like illness when infected with the Simian Immunodeficiency Virus (SIV). Many African primates harbor their own species-specific strain of SIV and chimpanzees are no exception. The host species for a particular SIV strain is indicated by a three letter abbreviation (all in lower-case) following the all-caps SIV. So, for chimpanzees, the strain is called SIVcpz. It turns out that there are two distinct HIVs, known as HIV-1 and HIV-2. HIV-1 is the virus that causes the majority of the world's deaths. It is what we call the "pandemic strain." HIV-2 is less pathogenic and has a distinct geographic focus in West Africa. The HIVs and the various SIVs belong to a larger group of viruses that infect a wide range of mammals known as the lentiviruses (lenti- meaning slow, referring to the slow time course of the pathology typically caused by these viruses). Collectively, we call the SIVs and HIVs "primate lentiviruses." Both HIV-1 and HIV-2 have well-documented origins in nonhuman primate reservoirs. HIV-2 is most closely related to SIVsmm, a virus that infects sooty mangebeys (a type of West-African monkey). HIV-1, on the other hand, is most closely related to SIVcpz, the virus that infects central and east African chimpanzees. We believe that both HIV-1 and HIV-2 entered humans hosts when hunters were contaminated with the blood of infected monkeys (HIV-2) or chimpanzees (HIV-1). Note that this means that our terminology for the primate lentiviruses is polyphyletic. SIVsmm and HIV-2 are sister species, while SIVcpz and HIV-1 are sister species. Yet we call all the viruses that infect nonhuman primates simian and all the viruses that infect humans human immunodeficiency viruses. It seems to me the best way to fix this would be to call the viruses that infect humans SIVhum1 and SIVhum2. Of course, that will never happen, but I do think that it's important to clarify the evolutionary history of these viruses.

A long-anticipated paper (by me anyway!) has finally been published in this week's issue of Nature. In this paper, we show that wild chimpanzees living in the Gombe National Park in western Tanzania on the shores of Lake Tanganyika appear to die from AIDS-like illness when infected with the Simian Immunodeficiency Virus (SIV). Many African primates harbor their own species-specific strain of SIV and chimpanzees are no exception. The host species for a particular SIV strain is indicated by a three letter abbreviation (all in lower-case) following the all-caps SIV. So, for chimpanzees, the strain is called SIVcpz. It turns out that there are two distinct HIVs, known as HIV-1 and HIV-2. HIV-1 is the virus that causes the majority of the world's deaths. It is what we call the "pandemic strain." HIV-2 is less pathogenic and has a distinct geographic focus in West Africa. The HIVs and the various SIVs belong to a larger group of viruses that infect a wide range of mammals known as the lentiviruses (lenti- meaning slow, referring to the slow time course of the pathology typically caused by these viruses). Collectively, we call the SIVs and HIVs "primate lentiviruses." Both HIV-1 and HIV-2 have well-documented origins in nonhuman primate reservoirs. HIV-2 is most closely related to SIVsmm, a virus that infects sooty mangebeys (a type of West-African monkey). HIV-1, on the other hand, is most closely related to SIVcpz, the virus that infects central and east African chimpanzees. We believe that both HIV-1 and HIV-2 entered humans hosts when hunters were contaminated with the blood of infected monkeys (HIV-2) or chimpanzees (HIV-1). Note that this means that our terminology for the primate lentiviruses is polyphyletic. SIVsmm and HIV-2 are sister species, while SIVcpz and HIV-1 are sister species. Yet we call all the viruses that infect nonhuman primates simian and all the viruses that infect humans human immunodeficiency viruses. It seems to me the best way to fix this would be to call the viruses that infect humans SIVhum1 and SIVhum2. Of course, that will never happen, but I do think that it's important to clarify the evolutionary history of these viruses.

The conventional wisdom regarding primate lentiviruses is that, with the exception of HIV, they are not pathogenic in their natural host. The reasoning for why HIV causes the devastating pathology that characterizes AIDS goes that HIV-1 is a relatively new infection of humans, having just spilled over into the human population recently. Pathogens that have recently crossed species boundaries are frequently highly pathogenic because neither the new host nor the pathogen has a history of coevolution with its new partner. While it is a pernicious myth (that just won't seem to die) that pathogens necessarily evolve toward a benign state, it is true that they frequently evolve a more intermediate level of virulence from their initial spillover virulence. There are a number of problems with the idea that HIV causes AIDS because it is poorly adapted to human physiology.

The first of these is that HIV-1 is not that recent an infection of humans. Sure, we didn't notice it until 1983 but careful molecular evolutionary analysis by Bette Korber of the Santa Fe Institute and my collaborator Beatrice Hahn and her group at the University of Alabama Birmingham puts the most likely date for the emergence of HIV-1 in humans to be 1931. That means that HIV-1 was being transmitted from human-to-human for over fifty years before it was ever noticed by western science. Fifty years, while certainly brief in evolutionary terms, is still long enough to lead to some reduction in virulence or host evolution.

The real nail in the coffin, however, is our new result. Specifically, we show that SIVcpz causes AIDS-like pathology in the Gombe chimpanzees. This result is surprising because (1) given it's pathogenicity, one would expect someone to have noticed it before, and (2) chimpanzees infected in captivity do not show obvious AIDS-like illness. I have been collaborating with Anne Pusey, Mike Wilson and their colleagues at the University of Minnesota's Jane Goodall Institute Center for Primate Studies on the the analysis of the demography of the Gombe chimps for a number of years now. Anne and Mike have, in turn, been collaborating with Beatrice Hahn with her project on monitoring natural SIV infection in wild chimpanzees across Africa. Given my background in HIV epidemiology and statistics, it was only natural that we all join forces to look at the demographic implications of SIV infection among the Gombe chimps. Jane Goodall famously started chimpanzee research at Gombe in 1960 and since 1964, researchers at Gombe have collected detailed demographic information, documenting all births, deaths, and migration events in the central community and eventually expanding to the peripheral ones in later years. As a result, we have an unmatched level of demographic detail (not to mention behavioral and ecological information) against which to assess the impact of SIV infection. Using statistical methods known collectively as event-history analysis, we were able to show that the hazard ratio between SIV-infected and SIV-negative chimps is on the order of 10-16. This essentially means that SIV+ chimps have mortality rates that are 10-16 times higher than uninfected chimps. The analysis controls for the clear potentially confounding effects of age and sex on overall mortality. The reason why no one ever noticed this heightened mortality rate is really because no one has ever looked for it. Even when a mortality rate is 10 times higher for some segment of a population, when that segment is small and when mortality rates quite low (chimps who survive infancy can live in excess of 40 years) it can be hard to detect even a seemingly large difference. This is why we do science: because things that seem obvious once we know they are there can be remarkably subtle when we don't know they're there. Science gives us the framework and the tools for studying nature's subtleties.

This project was absurdly interdisciplinary. The paper has 22 co-authors, each contributing his or her own particular analytical expertise or providing access to crucial data necessary for the larger narrative. There are papers in the literature in which people are made co-authors for pretty thin contributions. This paper has none of that. It was an extremely complicated story to tell and it really required the collaboration of this large team. Such work is not easy to manage and it's not at all easy to do well. I think that Beatrice should be commended for orchestrating all the various major contributions, keeping us in line and on schedule (more or less). It's really gratifying to see the excellent blog piece by Carl Zimmer in which he notes the virtues -- and the difficulty -- of combining various scientific styles in pursuit of an important question. The title of Carl's piece is "AIDS and the Virtues of Slow-Cooked Science." In addition, there is a nice companion piece in this week's Nature written by Robin Weiss and Jonathan Heeney. They too note the strength of the interdisciplinary approach to this problem.

The paper isn't even officially published until tomorrow and it has already been covered on Carl Zimmer's blog for Discover Magazine, The New Scientist, The Guardian, The Scientist, The New York Times and MSNBC. Wow. Weiss & Heeney note a number of questions that are raised by our analysis. Specifically, they ask "why was the progression to AIDS-like illness not more apparent in chimpanzees in captivity?" My co-author Paul Sharp notes "We need to know much more about whether there are any genetic differences among the chimpanzees, or differences in co-infections with other viruses, bacteria or parasites, which influence whether or not SIV infection leads to illness or death. This presents a unique opportunity to compare and contrast the disease-causing mechanisms of two closely related viruses in two closely related hosts." Then, of course, there are the conservation questions that this paper raises. Chimpanzees in the wild have birth rates that are very nearly balanced out by their death rates. This difference, called the intrinsic rate of increase, largely determines the probability of extinction of a small population. When the rate of increase of a population is negative, it is certain to go extinct (assuming the rate remains negative). However, even if the intrinsic rate of increase is greater than zero, the randomness that besets small populations still means that a population can go extinct. So, because their average birth and death rates are so close, individual chimp populations are certainly in potential jeopardy of going extinct, and Gombe is no exception to this rule. Now we add to a population something that increases mortality rates 10-16 times. This is bound to have negative consequences for the persistence of affected chimp populations. This is a topic that we are exploring even as I write...

Under-Reporting of Swine Flu

A very interesting epidemiological analysis of the first cases of novel A(H1N1) flu in China was posted on ProMED-mail this morning by Dr. Ji-Ming Chen, Head of the Laboratory of Animal Epidemiological Surveillance, China Animal Health and Epidemiology Center, Qingdao. Dr. Chen notes that all 12 of the cases in China were imported via air travel. He writes, "if the prevalence of the A (H1N1) infection among the international airplane passengers is comparable to that in the departure countries, there should be many more cases in USA and Canada than the official records (more than millions?)."

How can this be? There is more evidence in Chen's epidemiological analysis. Of the twelve imported cases, only two were identified as possible cases using airport temperature scanners. These two individuals were the only patients to complain of discomfort (i.e., flu-like symptoms) on their flights. It seems quite likely that this particular strain of influenza produces very mild, sub-clinical symptoms in many of its victims. The implication of this inference is that infection could become very widespread without being noticed by public health officials or the public at-large.

Daily Flu Counts

The bad news is that cases of novel 2009 influenza A(H1N1) continue to increase. Data from WHO Epidemic and Pandemic Alert and Response (EPR), Influenza A(H1N1) - update 43 — 23 May 2009:

The good news is that the spread appears to be sub-exponential at this point. Exponential growth will appear linear on semi-logarithmic axes. Here I plot the natural logarithms of these same case-count data against the date. We can see a distinct (negative) concavity, indicating that the growth in confirmed cases is sub-exponential. The usual caveats about under-reporting and the lag between infection and reporting dates apply, but this is a modicum of good news.

The austral flu season will be heating up (as it were) soon enough. Once again, it seems only prudent to me that the richer nations of the north help poorer nations, who are about to get hit, with efforts to contain the spread of novel A(H1N1). Given the relative genetic homogeneity of this novel strain, choice of a strain to include in a vaccine is straightforward (if a little late for the beginning of the northern flu season). If we can minimize the intensity of antigenic drift (despite the name which might imply random change, this is directional selection away the ancestral antigenic type in the presence of multiple circulating strains) by minimizing the number of cases in the south during their flu season, perhaps we can dodge the bullet of an extremely high-mortality pandemic.

Flu Case Counts for Today

Latest Swine Flu Counts

Data from WHO Epidemic and Pandemic Alert and Response (EPR), Influenza A(H1N1) - update 33 -- 19 May 2009:

More On Flu

There is a nice video piece at the New York Times website done by science reporter Donald G. McNeil Jr. In it, he makes a number of important points that I have been trying to emphasize in my latest posts on the topic. McNeil is to be congratulated. This is the kind of reporting we need now and in the coming months on swine flu.

The New Scientist also has an editorial (which I just found because I'm behind on my RSS reader) which notes the distinct possibility that H1N1 could come back with a vengeance this Fall. Note that most of the deaths in the pandemic of 1918 occurred in September of 1918 even though the first cases were reported in March of 1918. The pandemic of 1918 (which was really the pandemic of 1918-1920) killed 50 million people, perhaps as many as 100 million. The world population in 1920 was 1.86 billion, which means there were around 1.78 billion or so in 1918. The case fatality ratio for the 1918 flu was >2.5%, and perhaps as high as 5%, which means that 25-50 people died out of 1000 infected with the flu. All in all, this means that anywhere from 0.5% to 2% of the world's population died during the pandemic of 1918 (though if 100,000,000 people really died, then the overall world mortality rate was actually over 5%!). The following figure (from Taubenberger and Morens 2006) shows the time series of deaths from flu for 1918-1919.

The most striking feature of this figure is the pronounced spike in mortality in the Fall of 1918. We are currently a month before this time series starts in our current potential pandemic. Note that the death rate in June of 1918 was not too dissimilar from the mortality rate estimated from Mexican outbreak data by Fraser et al. (2009).

The New Scientist also reports that a flu vaccine incorporating the new A(H1N1) is unlikely to be available by the Fall of next year. This is, of course, distressing news. So, what can we do?

It seems to me that the best plan is to follow D.G. Margaret Chan's call for international solidarity. She has rightly noted that the people likely to be hardest hit by the an H1N1 pandemic (or any other infectious disease for that matter) are the citizens of the world's poor countries. They are the ones who bear 85% of the infectious disease burden, after all. So, why should we in the developed north care about this other half (homage to Yogi Berra intended)?

For the time-being the strain of A(H1N1) is relatively benign (just as it was in 1918 at this point), but influenza has an incredible capacity to mutate, recombine with other co-circulating flu strains, and respond to selection (the part that you don't typically hear about in news reports). Let us not forget that there is currently another highly pathogenic strain of flu out there. Highly pathogenic Influenza A(H5N1) -- remember bird flu? -- has an overall mortality rate of approximately 60%. Yes, that's an order of magnitude greater than the high-ball estimate for the 1918 flu. Of course, this variant of influenza has only infected a total of 424 people in the world since 2003. 141 of those have been in Indonesia (where 115 have died for a case fataility ratio of 81.5%). We have gotten very lucky so far with H5N1 because it is not efficiently transmitted from person-to-person. The emergent H1N1, however, is. It's basic reproduction ratio is substantially greater than that of seasonal flu, which indicates it is very efficiently transmitted. God help us if a recombinant strain with the pathogenicity of bird flu and the transmissibility of swine flu were to evolve.

This suggests to me that a little bit of financial and technical assistance from the north to the countries of the south might be a very good investment at this point. Let's help developing countries entering their flu season control swine flu to the absolute best degree we can manage. Minimizing the number of cases also minimizes the evolutionary potential of the virus -- fewer infections, fewer opportunities for mutation and subsequent selection. I realize that we are in the throes of a major economic crisis, the likes of which we haven't seen since 1929. But, do you have any idea what losing 5% of the world's population would do to the economy?

Keep Washing Your Hands

As the potential pandemic fades into the obscurity of a couple weeks' worth of the 24-hour news cycle, cases continue to mount. New York City reported its first swine-flu death, an assistant principal in a NYC public school. As with most of the other deaths so far, this particular victim had medical complications that contributed to his especially severe illness. This is typical for influenza and other serious respiratory illnesses like SARS. One of the greatest risk factors for dying of SARS during the outbreak of 2003 was being a diabetic (Chan et al. 2003). Flu is dangerous. As noted by Thomas R. Frieden, New York City's health commissioner and Obama appointee to head CDC, “We should not forget that the flu that comes every year kills about 1,000 New Yorkers.” As I noted in a previous post, analysis of the outbreak data from Mexico suggests that the current influenza A(H1N1) has a case fatality ratio a little bit higher than the usual seasonal flu, so we should expect it to kill more people, though not dramatically more.

The number of cases continues to rise in Japan, another northern hemisphere country with high-functioning public health infrastructure, despite how late in the season it is. The Japanese government has closed over a thousand schools around the western cities of Kobe and Osaka in an attempt to curtail transmission. So far, there does not appear to be sustained community transmission, but again, it is remarkable that there is any transmission to speak of this late in the flu season. One other troubling part of this particular outbreak is that the school cluster around Kobe and Osaka is not associated with overseas travel as clusters in the United States and Europe have been.

WHO Director General Margaret Chan announced at the recent meeting of the World Health Assembly that the apparent quiescence of flu activity now -- even as WHO has kept its pandemic alert at level 5 -- could still be “just the calm before the storm.” She urged countries to work together to continue to control the current outbreak of A(H1N1), noting that those most vulnerable remain the poorest of the world's citizens. As quoted in the NY TImes, “I strongly urge the international community to use this grace period wisely. I strongly urge you to look closely at anything and everything we can do, collectively, to protect developing countries from, once again, bearing the brunt of a global contagion.”

Just to highlight the fact that, despite the media silence, the swine flu outbreak continues to grow globally, I will post an updated plot of the WHO case counts for today.

Yes, cases continue to rise. Let's continue to take reasonable personal precautions, help with the battle against flu in countries of the southern hemisphere, and prepare for the next flu season here. It never hurt anyone to wash their hands a couple more times a day.

Pssst, Swine Flu is Still Here

The coming Aporkalypse appears to have faded into last week's obscurity. With WHO raising the pandemic alert from 3 to 5 in the span of about 24 hours, it seemed that Oinkmageddon was upon us. But now it's hard to find a news piece on swine flu, let alone an inflammatory one. This is something that worries me and lots of other public health professionals. Not so much the lack of inflammatory new pieces. More, I worry that people are going to see this incident of just another case of health officials needlessly pushing the panic button. There is always the possibility that the public health measures enacted to control extensive spread of Influenza A(H1N1) may have actually worked! The epidemic fizzling when the alert goes to level 5 is really the best possible case, right? Alas, I doubt that it's really the case. As I noted before, it seems unlikely that we will have extensive sustained transmission in the northern hemisphere at this late date. But case counts continue to grow globally and the austral flu season starts in the not-too-distant future.

WHO publishes case counts each day, and I have plotted them from 30 April through 13 May. These are the worldwide confirmed cases as of this morning.

We can see that the case count does, in fact, increase each day and shows no sign of slowing down. This is true, incidentally, whether one plots the cumulative number of the incident number -- clearly this plot is more dramatic, but the incidence does not show any obvious sign of decline. Of course, there is an inherent lag in the reporting of confirmed cases, so it is at least possible that the number of cases has peaked. But I doubt it. Recent analysis by an international team of epidemiologists suggests that the reproduction number (the average number of secondary cases produced by a single primary case in a completely susceptible population) is substantially greater than that of seasonal flu. The reproduction number tells us how fast and how far an infectious disease will spread and how many people will ultimately be infected and higher values of the reproduction number mean faster, further and more. This team also found that the estimated case fatality ratio is less than that of the 1918 pandemic strain but comparable to the 1957 pandemic strain. So, given proper environmental conditions for transmission, this variant of the flu looks like it could spread rapidly, widely, and cause a decent amount of mortality. It seems entirely possible that this is exactly what will happen in the southern hemisphere in the coming months, after which it will come back and hit here in the north.

We can see that the case count does, in fact, increase each day and shows no sign of slowing down. This is true, incidentally, whether one plots the cumulative number of the incident number -- clearly this plot is more dramatic, but the incidence does not show any obvious sign of decline. Of course, there is an inherent lag in the reporting of confirmed cases, so it is at least possible that the number of cases has peaked. But I doubt it. Recent analysis by an international team of epidemiologists suggests that the reproduction number (the average number of secondary cases produced by a single primary case in a completely susceptible population) is substantially greater than that of seasonal flu. The reproduction number tells us how fast and how far an infectious disease will spread and how many people will ultimately be infected and higher values of the reproduction number mean faster, further and more. This team also found that the estimated case fatality ratio is less than that of the 1918 pandemic strain but comparable to the 1957 pandemic strain. So, given proper environmental conditions for transmission, this variant of the flu looks like it could spread rapidly, widely, and cause a decent amount of mortality. It seems entirely possible that this is exactly what will happen in the southern hemisphere in the coming months, after which it will come back and hit here in the north.

As I noted before, I can hope is that people have not become inured to warnings of epidemics because of our recent experience with H5N1 bird flu and this new H1N1 swine flu (there is also the last swine flu scare of 1976). Some saner press coverage would help. Of course, it would mean less grist for the mills of John Stewart and Stephen Colbert, but it might mean a public better prepared for a potentially real public health emergency that we still may face.

Uncertainty and Fat Tails

A major challenge in science writing is how to effectively communicate real, scientific uncertainty. Sometimes we just don't know have enough information to make accurate predictions. This is particularly problematic in the case of rare events in which the potential range of outcomes is highly variable. Two topics that are close to my heart come to mind immediately as examples of this problem: (1) understanding the consequences of global warming and (2) predicting the outcome of the emerging A(H1N1) "swine flu" influenza-A virus.

Harvard economist Martin Weitzman has written about the economics of catastrophic climate change (something I have discussed before). When you want to calculate the expected cost or benefit of some fundamentally uncertain event, you basically take the probabilities of the different outcomes and multiply them by the utilities (or disutilities) and then sum them. This gives you the expected value across your range of uncertainty. Weitzman has noted that we have a profound amount of structural uncertainty (i.e., there is little we can do to become more certain on some of the central issues) regarding climate change. He argues that this creates "fat-tailed" distributions of the climatic outcomes (i.e., the disutilities in question). That is, the probability of extreme outcomes (read: end of the world as we know it) has a probability that, while it's low, isn't as low as might make us comfortable.

A very similar set of circumstances besets predicting the severity of the current outbreak of swine flu. There is a distribution of possible outcomes. Some have high probability; some have low. Some are really bad; some less so. When we plan public health and other logistical responses we need to be prepared for the extreme events that are still not impossibly unlikely.

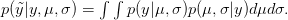

So we have some range of outcomes (e.g., the number of degrees C that the planet warms in the next 100 years or the number of people who become infected with swine flu in the next year) and we have a measure of probability associated with each possible value in this range. Some outcomes are more likely and some are less. Rare events are, by definition, unlikely but they are not impossible. In fact, given enough time, most rare events are inevitable. From a predictive standpoint, the problem with rare events is that they're, well, rare. Since you don't see rare events very often, it's hard to say with any certainty how likely they actually are. It is this uncertainty that fattens up the tails of our probability distributions. Say there are two rare events. One has a probability of  and the other has a probability of

and the other has a probability of  . The latter is certainly much more rare than the former. You are nonetheless very, very unlikely to ever witness either event so how can you make any judgement that the one is a 1000 times more likely than the other?

. The latter is certainly much more rare than the former. You are nonetheless very, very unlikely to ever witness either event so how can you make any judgement that the one is a 1000 times more likely than the other?

Say we have a variable that is normally distributed. This is the canonical and ubiquitous bell-shaped distribution that arises when many independent factors contribute to the outcome. It's not necessarily the best distribution to model the type of outcomes we are interested in but it has the tremendous advantage of familiarity. The normal distribution has two parameters: the mean ( ) and the standard deviation (

) and the standard deviation ( ). If we know

). If we know  and

and  exactly, then we know lots of things about the value of the next observation. For instance, we know that the most likely value is actually

exactly, then we know lots of things about the value of the next observation. For instance, we know that the most likely value is actually  and we can be 95% certain that the value will fall between about -1.96 and 1.96.

and we can be 95% certain that the value will fall between about -1.96 and 1.96.

Of course, in real scientific applications we almost never know the parameters of a distribution with certainty. What happens to our prediction when we are uncertain about the parameters? Given some set of data that we have collected (call it  ) and from which we can estimate our two normal parameters

) and from which we can estimate our two normal parameters  and

and  , we want to predict the value of some as-yet observed data (which we call

, we want to predict the value of some as-yet observed data (which we call  ). We can predict the value of

). We can predict the value of  using a device known as the posterior predictive distribution. Essentially, we average our best estimates across all the uncertainty that we have in our data. We can write this as

using a device known as the posterior predictive distribution. Essentially, we average our best estimates across all the uncertainty that we have in our data. We can write this as

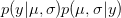

OK, what does that mean?  is the probability of the data, given the values of the two parameters. This is known as the likelihood of the data.

is the probability of the data, given the values of the two parameters. This is known as the likelihood of the data.  is the probability of the two parameters given the observed data. The two integrals mean that we are averaging the product

is the probability of the two parameters given the observed data. The two integrals mean that we are averaging the product  across the range of uncertainty in our two parameters (in statistical parlance, "integrating" simply means averaging).

across the range of uncertainty in our two parameters (in statistical parlance, "integrating" simply means averaging).

If you've hummed your way through these last couple paragraphs, no worries. What really matters are the consequences of this averaging.

When we do this for a normal distribution with unknown standard deviation, it turns out that we get a t-distribution. t-distributions are characterized by "fat tails." This doesn't mean they look like this. What it means is that the probabilities of unlikely events aren't as unlikely as we might be comfortable with. The probability in the tail(s) of the distribution approach zero more slowly than an exponential decay. This means that there is non-zero probability on very extreme events. Here I plot a standard normal distribution in the solid line and a t-distribution with 2 (dashed) and 20 (dotted) degrees of freedom.

We can see that the dashed and dotted curves have much higher probabilities at the extreme values. Remember that 95% of the normal observations will be between -1.96 and 1.96, whereas the dashed line is still pretty high for outcome values beyond 4. In fact, for the dashed curve, 95% of the values fall between -4.3 and 4.3. In all fairness, this is a pretty uncertain distribution, but you can see the same thing with the dotted line (where the 95% internal interval is plus/minus 2.09). Unfortunately, when we are faced with the types of structural uncertainty we have in events of interest like the outcome of global climate change or an emerging epidemic, our predictive distributions are going to be more like the very fat-tailed distribution represented by the dashed line.

As scientists with an interest in policy, how do we communicate this type of uncertainty? It is a very difficult question. The good news about the current outbreak of swine flu is that it seems to be fizzling in the northern hemisphere. Despite the rapid spread of the novel flu strain, sustained person-to-person transmission is not occurring in most parts of the northern hemisphere. This is not surprising since we are already past flu season. However, as I wrote yesterday, it seems well within the realm of possibility that the southern hemisphere will be slammed by this flu during the austral winter and that it will come right back here in the north with the start of our own flu season next winter. What I worry about is that all the hype followed by a modest outbreak in the short-term will cause people to become inured to public health warnings and predictions of potentially dire outcomes. I don't suppose that it will occur to people that the public health measures undertaken to control this current outbreak actually worked (fingers crossed). I think this might be a slightly different issue in the communication of science but it is clearly tied up in this fundamental problem of how to communicate uncertainty. Lots to think about, but maybe I should get back to actually analyzing the volumes of data we have gathered from our survey!